How Bitcoin can prevent wars

Part 1: Coin debasements

There are few topics on which people are usually as united as on the subject of war. As a rule, you only receive support if you express your opposition to wars and the associated deaths of countless innocent people.

One aspect that is often neglected in the discussion about wars is money. Wars cost vast amounts of money. Money that the belligerent states have to raise. As a rule, tax revenues are not sufficient for this, so the type of money plays a central role.

This multi-part series of articles will use examples from the past to show how wars have been financed and what role the type of money has played in this. In addition, arguments will be presented to show that Bitcoin, as the world's money, can prevent wars.

War and the devaluation of money

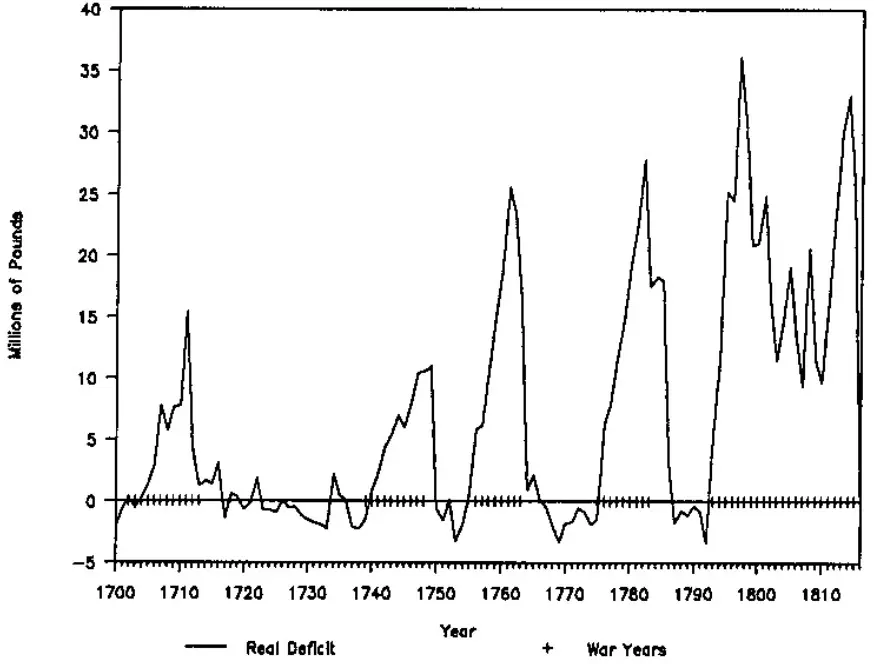

If you look at the national debt (debt in relation to gross domestic product) of the most relevant economies over the last few centuries, a pattern emerges. In the UK and the USA, local peaks in national debt clearly correspond to major wars in which the country was involved. The nations had to take on a relatively large amount of debt because the tax revenues were obviously not enough.

How easily a state can borrow money depends not least on the type of money. In a fiat money system, as is the case today, the central bank can theoretically lend the state an unlimited amount of newly printed money. If a state borrows more money from its own central bank, this is usually at the expense of those who save in the national currency or in government bonds. More on this in the Blocktrainer.de article on financial repression.

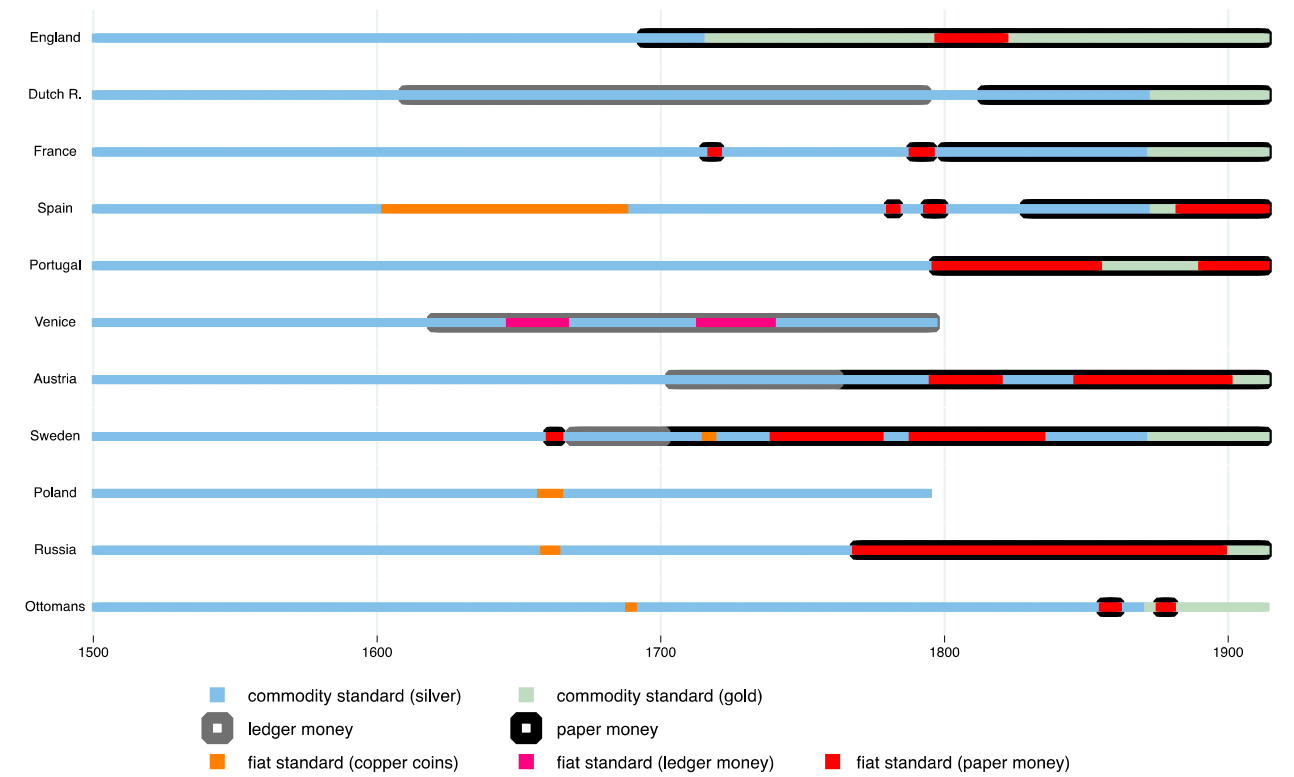

If we look further back in time, wars also went hand in hand with the devaluation of money. Karaman et al. found that in the period from 1500 to 1910 there was a significant correlation between wars and the devaluation of money in Europe - to a lesser extent also in civil wars.

The states devalued [the currency] less when executive power was restricted and more when they were under war pressure. Both variables are significant at the 0.1% level. Civil wars were also associated with devaluations, but at the 10% level or less.

There is ample evidence in the monetary history literature that the fiscal demands of warfare were by far the most important cause of devaluations.

Karaman et al: "Money and monetary stability in Europe, 1300-1914"

However, the type of money was only indirectly the problem. In Europe during this period, people mainly traded in silver and gold coins. Nevertheless, there were long and brutal wars. This can be explained by the fact that governments usually minted the coins. If they needed more money, for example to wage wars, they reduced the precious metal content. They usually did this by collecting the population's coins, melting them down and minting new ones with a lower material value. Until the 18th century, this was an extremely common practice for raising funds in times of war.

How and to what extent coin debasement took place during wars and how (central) banks and paper money emerged over time to facilitate war financing will now be shown using a few examples. As it would go beyond the scope of this article to start with "Adam and Eve", we will concentrate on the period from the 14th century onwards.

Hundred Years' War (1337 - 1453)

The Hundred Years' War was one of the longest wars in Europe. It pitted France against England, but other regions were also involved. In order to finance the war, various governments and territories devalued their currencies. The result was instability in the monetary system, including inflation, and a worsening economic situation. However, England managed to cover the majority of the war costs through extremely high taxes and levies - this was to remain an exception.

[...] the French, Flemish, Brabantine, Aragonese and various Italian governments, to name but a few, attempted to finance and facilitate the cash flows necessary for the war effort by drastically debasing coinage, sometimes so severely that it triggered a veritable "coin flight". However, the English crown was a unique exception to these currency manipulations: Here it made only a single, relatively minor reduction in the weight of silver coins in 1351 and thereafter maintained a perfectly stable coinage in both metals until 1411/12.

John Munro: "Money, Prices, and Wages in Fourteenth-Century England"

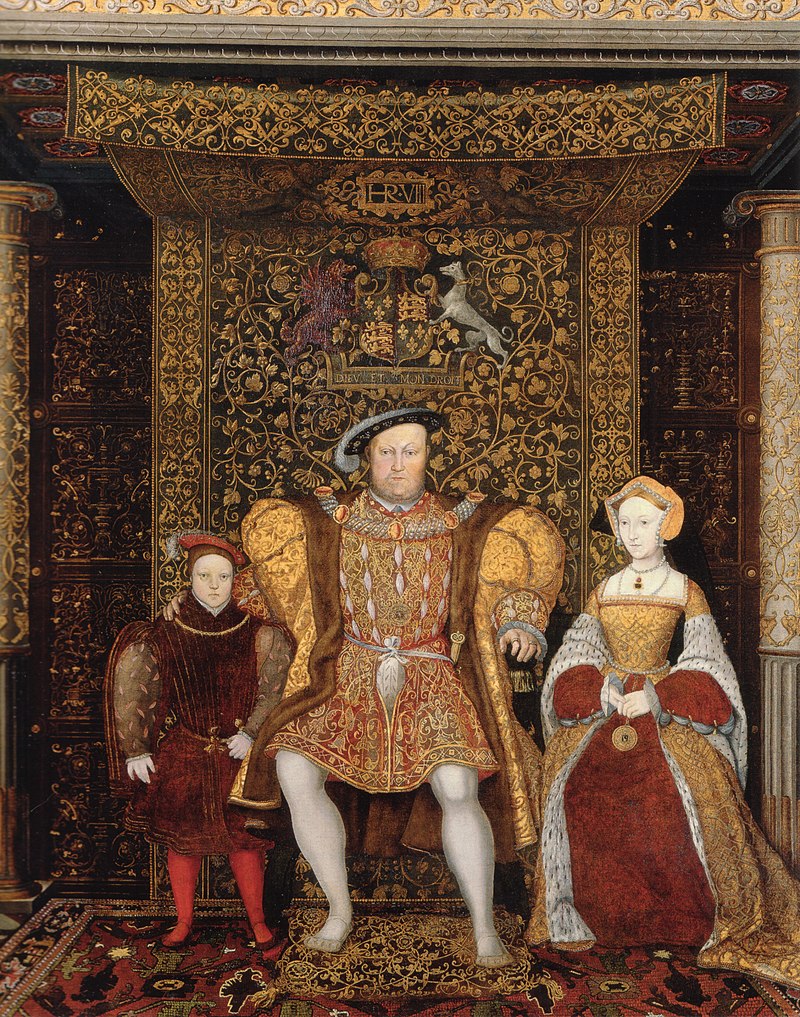

England in the mid-16th century provides an impressive example of how governments reduced the precious metal content of coins in order to finance wars as well as their decadent lifestyle. Kings Henry VIII and Edward VI, who succeeded his father as king after the latter's death in 1547, are remembered for the sharp devaluation of money. In retrospect, this period is also known as The Great Debasement.

Henry lived very lavishly and was very overweight - shortly before his death he weighed 160 kg. The king was also known for his love of war. After his funds were exhausted by the wars against France, he secretly reduced the silver content of the coins within a few years in order to finance the war of aggression against Scotland(Rough Wooing). His successor followed suit.

For around 400 years, England had maintained a purity of 92.5 percent for the pound sterling, but with Henry's debasement, the purity of the coins gradually fell to 75 percent, then to 50 percent, to 33 percent and finally to 25 percent. An issue of 1551 under Edward VI contained only 17 percent of the silver that was contained in the issues before the debasement. As a result, the former prestige of the English coins, which had at times been the envy of northern Europe, was quickly eroded.

Stephen Deng: "The Great Debasement and Its Aftermath"

Eighty Years' War (1568 - 1648)

During the Eighty Years' War, the Netherlands, then the crossroads of the world, fought for its independence from Spain. In 1609, during the war, the Amsterdam Exchange Bank was founded. The publicly owned bank made cashless settlement of claims possible for the first time and is regarded as the forerunner of today's central banks. In addition, the exchange bank of the Netherlands, which also emerged victorious from the war, made it possible for the first time to issue tradable war bonds on the market and thus collect additional money.

Another important change occurred after 1610, when the Dutch states began to use bonds instead of annuities as the main means of credit.

Gelderblom & Jonker: "Exploring the market for government bonds in the Dutch Republic (1600-1800)"

Thirty Years' War (1618 - 1648)

The Thirty Years' War is considered one of the most brutal wars ever. Hardly any other war led to such a drastic population reduction in relative terms - in the affected regions, the population is estimated to have been reduced by a third. The battle took place primarily between Protestants and Catholics in Germany, but other European countries and rulers were also involved.

In the context of the war, there is also talk of the tipper and wipper period. This term refers to the practice of weighing (rocking) circulating coins and sorting out (tipping) those with a higher silver content in order to mint new coins from them with the addition of copper.

This ultimately took place on a state-organized level during the war. Almost all princes felt compelled to devalue their coins further and further. The so-called tippers and wippers were used by the sovereigns for this purpose. In the Duchy of Brunswick, for example, the coins in 1619 were already only half the prescribed silver content - in 1620 only a third.

Mints sprang up like mushrooms everywhere. In fact, some states even imitated the coins of other states in even lower quality in order to export them there. Over time, the coins circulating in Europe were made exclusively of copper. A boom-and-bust cycle and hyperinflation were the result.

The war further increased the princes' need for revenue and prepared the ground for the hyperinflation that followed. [...] The initial effect of the enormous expansion of the money supply was an economic boom. But eventually prices began to rise rapidly, and the initial boom turned into hyperinflation and crisis.

Schnabel & Shin: "Money and trust: lessons from the 1620s for money in the digital age"

First central bank in the world

After all, Sweden is the first European country to declare uncovered paper money (fiat money) to be legal tender.

What was new about the Palmstruch banknotes was that they were not tied to a deposit. Instead, they were based on the public's trust that the bank would pay out the value of the banknote in coins on demand.

Swedish Riksbank

The Palmstrutch Bank was founded in 1656 and taken over by the Swedish National Bank in 1668. It was modeled on the Amsterdam Exchange Bank, which, unlike the Swedish National Bank, no longer exists today. Depending on the definition, the Swedish National Bank is referred to as the world's first central bank.

The Palmstrucht Bank was granted a monopoly on the issue of uncovered paper money in 1661 - two years later there was already severe inflation in Sweden and a few years later the bank failed, but the state stepped in and took it over. The reason for the switch to a fiat money system can be found, as expected, in the war: After the Thirty Years' War, Sweden was in financial distress.

In 1701, the issuing of banknotes was resumed and private banks were also allowed to issue their paper money, which was exchangeable for the banknotes of the Swedish National Bank. At this time, Sweden was involved in the Great Northern War (1700 - 1721) and when this went in Sweden's favor, the first bank run in history took place - the citizens' money was ultimately frozen.

Many people had deposited money in the bank, but after Sweden's crushing defeat at Poltava in 1709, they became frightened. They rushed to the bank to withdraw their savings. But as the bank had lent the king so much money, there was not enough left. The bank simply closed its counters and froze the depositors' accounts on the grounds that everyone had to contribute to the war effort.

Swedish Riksbank

Bank of England emerges in war

The Bank of England was founded in 1694 during the War of the Palatinate Succession (1688 - 1697). England lost thenaval battle of Beachy Head (1690) against France and had to rebuild its navy. However, due to its poor credit rating, it was not possible to find lenders on good terms. With the founding of the Bank of England, however, this was possible and England was able to obtain the necessary funds at an interest rate of 8 percent, which was low by the standards of the time.

Without the Bank, these crises would have impaired Britain's ability to wage war [...].

O'Brien & Palma: "The Bank of England and the British economy, 1694-1844"

In return, creditors gave the Bank their precious metals and received negotiable bonds, which they could in turn convert into paper money. Paper money increasingly developed into a means of payment. Shortly afterwards, during the war, redeemability was already suspended.

Two years after its foundation, the bank experimented for the first time with the suspension of payments [...]. To buy government debt, the Bank of England issued £760,000 worth of banknotes, which had an immediate inflationary impact on the British economy. There was a run on the bank and the central bank became insolvent. In May 1696, Parliament allowed the bank to suspend the payment of coins.

Duryea: "William Pitt, the Bank of England"

For the next 100 years, however, paper money was redeemable in coins most of the time. The Bank of England finally gained a monopoly on the issue of paper money in 1708, during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 - 1714). Technically, England was on a gold standard, but the wars were still financed with unbacked debt or credit money.

British war expenditure was financed primarily by the issue of uncovered debt, a variety of short-term obligations, including naval, ordinance and, increasingly, currency bills.

Bordo & White: "British and French Finance During the Napoleonic Wars"

Despite the gold standard, the money supply was expanded as required.

The Bank of England exercised [...] an impressive power over the money supply, which made it easier for Britain to engage in military conflicts without attracting private investors for loans.

Duryea: "William Pitt, the Bank of England"

Britain was therefore able to wage several wars on this type of gold standard. During the wars, the state borrowed money with the help of the Bank of England and after the wars it reduced its debts again. Despite all this, England's national debt continued to reach new highs in the 18th century, as the graph in the introduction to the article shows.

As a result of Britain's involvement in numerous wars in the 18th century, including Queen Anne's War, the War of Jenkins' Ear, the French and Indian War and the American War of Independence, a massive national debt was built up.

Duryea: "William Pitt, the Bank of England"

Fiat money in France

Something similar to Sweden occurred in France at the beginning of the 18th century. The state was heavily in debt due to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 - 1714) and the decadence of the royal family. In 1716, the Scottish economist John Law, who was known for his gambling addiction, persuaded the French government to introduce fiat money - so that the state could reduce its debts. Law became finance minister and founded the Banque Générale central bank. Initially, the promise was that paper money could be exchanged for gold and silver. The large amount of paper money created by the fractional reserve system triggered an economic boom and the great financial market bubble(Mississippi bubble 1718 - 1720). Finally, when the citizens triggered a bank run out of mistrust, redeemability was suspended. Hyperinflation was the result, the fiat money system failed and John Law, who was seen as a fraudster in this context, fled to Belgium.

In 1768, Russia also introduced fiat money for the first time in the form of the assignation rouble. The Assignation Bank was founded for this purpose in the same year. After the Seven Years' War (1756 - 1763), for which the silver coins already had to be significantly devalued, the Russian government lacked the funds. However, when fiat money was introduced in 1768, following the example of John Law, Russia was able to start three new wars immediately: the Russo-Turkish War (1768 - 1774), the war against the Confederation of Bar (1768 - 1772) and the Koliivshchyna Rebellion (1768 - 1769).

Word of John Law's fame had spread as far as St. Petersburg and, despite the disaster of his venture, Peter the Great tried to persuade the Scottish financier to try again in Russia. However, the first two Russian banks to issue paper money were not founded until 1768 under the reign of Catherine II. The amount of paper money, originally limited to one million roubles, rose to 156 million in 1796 and to 846 million in 1817, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars. After convertibility into silver had been suspended in 1777, the paper ruble was quoted at 68 percent of its face value in 1796 and at 20 percent in 1808, a historic low.

Florinsky: "Inflations: Russia-The U.S.S.R."

Fiat money is war money

It should now be clear that there is a clear connection between wars and the emergence of fiat money. Although it would go beyond the scope of this article to explain every change in the monetary system and the link to wars, we still have the clearest examples of this observation ahead of us - and it is not just the First World War.

Preview

[The graph] also confirms that wars and fiscal emergencies triggered a shift to the fiat standard. This pattern is most evident during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. During this period, fiscal pressure forced seven countries in our sample to suspend convertibility. While the Napoleonic era is the most obvious example, the role of wars and fiscal distress in forcing states to suspend convertibility can be applied to other fiat episodes in our sample.

Karaman et al: "Money and monetary stability in Europe, 1300-1914"

Interim conclusion

Even when people traded in silver coins, governments were able to heavily debase the official means of payment in order to tap into additional income streams. This was eventually taken to extremes during the Thirty Years' War. With the emergence of central banks, there were also the first attempts to implement unbacked paper money or credit money and shortly afterwards the first bank run during the Great Northern War - customer deposits were frozen.

Bitcoin as the world's money would make it impossible for circulating units to be devalued under duress and force or even secretly. The special thing about Bitcoin is that the quantity is verifiably limited and this can never be changed by individual entities, such as governments. Bitcoin also means that you do not have to trust a (central) bank - you can store your money yourself and still carry out transactions in a digitalized and globalized world. Bitcoin can therefore also protect against bank deposits being frozen because they are to be passed on to the government for warfare, for example, or against credit money being used to create more banknotes than underlying money.

It is also important to mention that knowing that the money can still be devalued in an emergency after the war in order to inflate away the war debts can also encourage wars.

However, the question of whether and how Bitcoin as money would prevent wars is much more complex and will be dealt with in more detail in the coming articles.