How Bitcoin can prevent wars

Part 2: Uncovered paper money

In the first part of this series of articles, we looked at some examples in which governments in Europe deliberately debased coins in order to finance wars. We also took a look at the emergence of central banks and the first attempts to issue fiat money in connection with wars.

The focus of the second part of the series is the issue of uncovered paper money for warfare. There are already a number of examples of this in the period from the 17th to the 19th century.

As this was the beginning of the period in which the USA emerged and gained relevance, it is worth taking a look across the Atlantic. Here, too, it is easy to see the connection between fiat money and wars:

Fiat money in New England

Before the American War of Independence and the creation of the USA, the American colonies had already introduced paper money to finance war. For example, during the War of the Palatine Succession or King William's War (1689 - 1697) to finance an attack on Canada:

In 1690, Massachusetts inadvertently introduced a [...] type of fiat money, ''Bills on Credit'', when the colony issued certificates - short-dated government bonds - to finance its attack on Quebec during King William's War (1689 - 1697). The colonial government intended to redeem the certificates quickly through tax revenues [...].

Humpage: "Paper Money and Inflation in Colonial America" (Cleveland Fed)

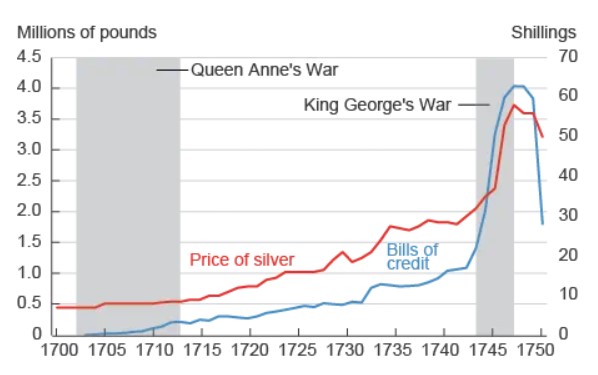

During the War of the Spanish Succession or Queen Anne's War (1702 - 1713 ), the colonies, led by Massachusetts, also issued paper money to cover the costs of the war - the money supply multiplied:

Massachusetts issued paper money several times to finance its participation in Queen Anne's War (1702 - 1713). Over the next 10 years, the stock of paper money in Massachusetts increased by an incredible 39 percent per year (annual growth rate). Between 1703 and 1713, the amount of paper money circulating in New England had increased at least 34-fold.

Humpage: "Paper Money and Inflation in Colonial America" (Cleveland Fed)

The issue of unbacked paper money was finally taken to extremes during the War of the Austrian Succession or King George's War (1743 - 1748) - in comparison, the previous paper money issues and their consequences were a joke. In retrospect, this period is also known as the Great Inflation of New England.

Inflation became a growing, damaging problem in New England, but it exploded during King George's War (1743 - 1748). To finance the conflict, the New England colonies again resorted to issuing huge amounts of paper money. During these years, the stock of paper money grew by 24.3 percent per year (annual growth rate).

Humpage: "Paper Money and Inflation in Colonial America" (Cleveland Fed)

In response to the great inflation, the New England parliament passed the Currency Act in 1751. This was intended to ensure that paper money was only issued to a limited extent and secured by the state. In addition, money holders had to be compensated for any loss of purchasing power of their money.

During the Seven Years' War in North America , or French and Indian War (1754 - 1763), the colonies again issued large amounts of paper money to finance the war. However, as these were secured by mortgage and tax payments, there was no major inflation.

Pennsylvania, New York and South Carolina used fiduciary standards to issue large amounts of paper money to finance the [Seven Years'] War.

Wicker, "Colonial Monetary Standards Contrasted: Evidence from the Seven Years' War"

American War of Independence (1775 - 1783)

In the American War of Independence, also known as the Revolutionary War, the American colonies fought for independence from England - in the war, the United States of America (USA) was formed. Before the war, around ten million dollars were in circulation in the form of gold and silver coins. Due to a poor credit rating, the government decided to issue two million dollars in uncovered paper money, called continentals, in the year the war began in order to cover the costs of the war. The missing precious metal was then to be collected through taxes over the next few years.

Initially, confidence in the continentals, which were also exchangeable for gold and silver, was strong. This led the government to print more and more continentals, even though it had only planned to issue two million:

Congress issued six million dollars of Continentals in 1775, and the issues [of paper money] increased year by year. In 1779, one hundred and forty million [Continentals] were issued. As prices rose, the government found that it needed more and more dollars to finance its expenditures. More money was printed. This additional supply of dollars led to further devaluation in the infamous spiral of inflation. At the beginning, the Continental was circulating at the same value as a coin dollar. By 1780, more than one hundred Continentals were required to exchange one coin dollar; Congress had printed Continentals until they were worth almost nothing.

Murray Rothbard: "Not Worth a Continental"

With the Declaration of Independence signed in 1776, the Currency Act of 1751 was no longer in effect and because the Continentals ultimately lost so much value, the saying "not worth a Continental" developed.

The government shifted the blame for the devaluation away from itself. On the one hand, the ''greedy merchants who are only out to make a profit'' were blamed for the rising prices. On the other hand, the people who refused to accept the paper money were vilified by the state as ''enemies of the country''. The USA drifted into a planned economy, including price controls, with disastrous consequences for the economy.

In 1780, Congress announced that continentals could be exchanged for coinage dollars (silver) at a rate of 40:1 with the state via taxes - but this was ultimately by no means the case everywhere:

In the worst cases, in Georgia and Virginia, it was accepted in payment of taxes at a ratio of $1,000 in paper money to $1 in silver. [...] New York was more representative and accepted its paper money in payment of taxes at the rate of $128 in paper money for $1 in silver. In Pennsylvania, the state accepted its paper money at a rate of $175 for $1.

Thies: "Not Worth a Continental"

The Napoleonic era

As already mentioned in the first article, the Napoleonic era is one of the most obvious examples of the suspension of convertibility or the introduction of fiat money in Europe to finance wars - at least in the period up to the First World War.

The French Revolution began with a civil war (Vendée Revolt (1789 - 1792)) in which France issued fiat money without restraint. This is also the first, but not the last, example of fiat money issues in civil wars. The revolution eventually led to the Napoleonic Wars, which in turn led other countries to resort to printing money to finance war.

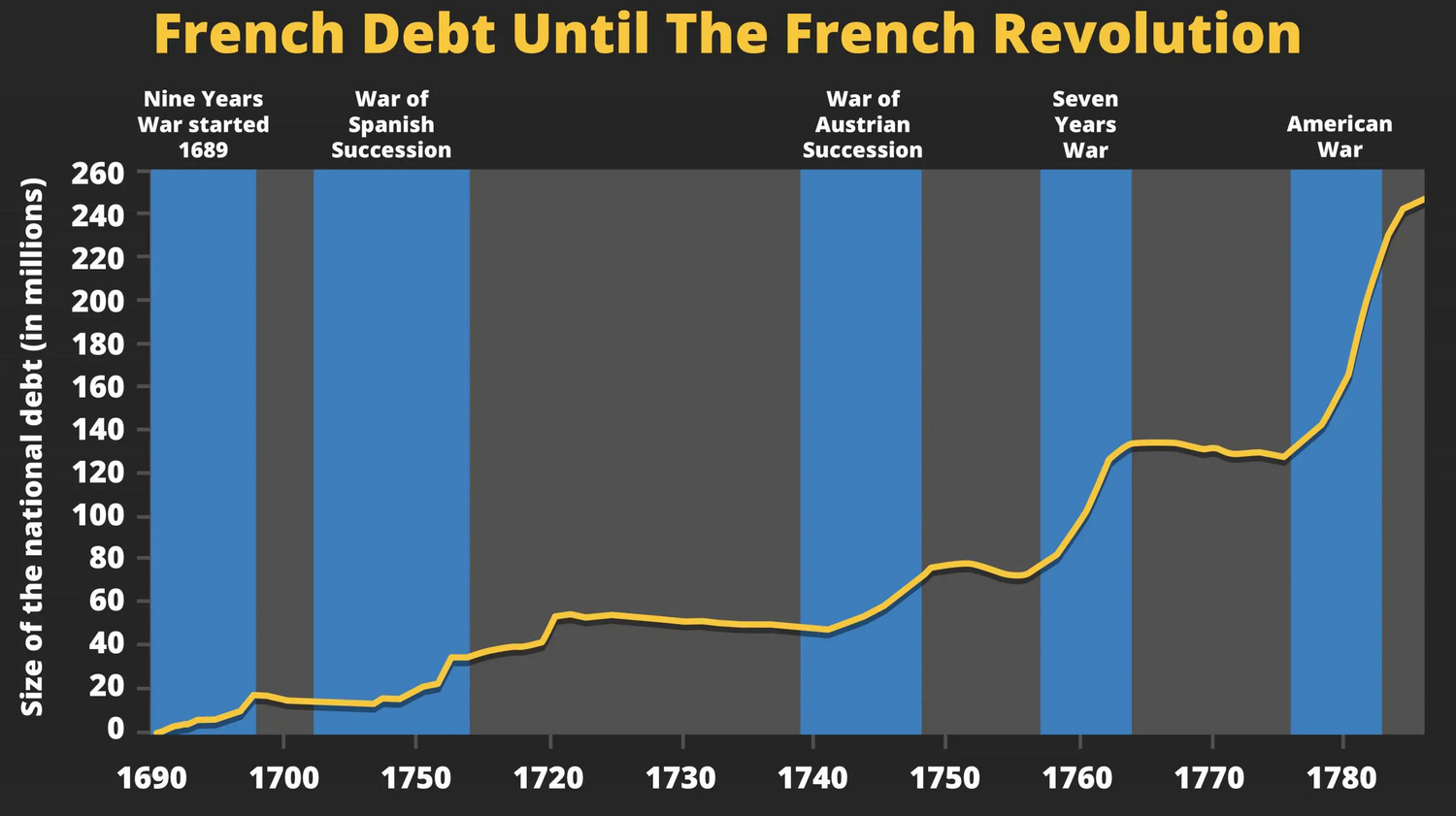

Before the French Revolution, the French state budget was in a precarious situation. The state consistently spent more than it took in and the national debt kept climbing to new heights. This was due in particular to the Seven Years' War (1756 - 1763) and the American Revolution (1775 - 1784), in which France was involved. The construction and maintenance of the Palace of Versailles and the lavish lifestyle of the royal family exacerbated the situation.

All of this resulted in high taxes, which were borne exclusively by the poorer sections of the population. In addition, the government monitored almost all trade, which further damaged the economy. Due to the poor economic situation and the perceived injustices, the French Revolution and the Vendée Uprising broke out.

The revolutionary forces and the new rulers directly expropriated the church. They then introduced the assignat. They paid the paper money to the state's lenders on the promise that they could use it to buy the previously expropriated land. The assignats became a means of payment, the money supply was continually expanded and the possession of gold and silver was banned. Attempts to counteract the rising prices with price controls were in vain - hyperinflation was inevitable.

On March 17, 1790, the revolutionary National Assembly decided to issue a new paper currency called the Assignat and 400 million units were put into circulation in April. As the government was short of funds, it put another 800 million into circulation at the end of the summer. By the end of 1791, 1.5 billion assignats were in circulation and purchasing power had fallen by 14 percent. In August 1793, the number of assignats had risen to almost 4.1 billion and their value had fallen by 60 percent. In November 1795 there were 19.7 billion assignats and by this time the purchasing power had fallen by 99 percent since the first issue. In less than five years, the money of revolutionary France had become worth less than the paper it was printed on.

Ebeling: "The Great French Inflation"

After the Assignat had failed, there was another attempt in 1796: a new uncovered paper money called the Mandat was introduced, but also failed a few months later due to hyperinflation. At the same time, Napoleon launched the Italian campaign (1796 - 1797), which is part of the Revolutionary Wars.

Although France drastically reduced its national debt as a result of the revolution, the debt burden was still too high and France's credibility was squandered.

France

After the revolution, France under Napoleon then attacked some countries in order to impose the new French ideals on others. However, due to the loss of credibility, France had no choice but to finance the Napoleonic wars primarily through taxes. By the time of the wars, France was back on a gold and silver standard. During the wars, in 1800, Napoleon founded the French central bank Banque de France. Although the banknotes issued were (most of the time) exchangeable for gold and silver, they made it easier for Napoleon to finance the war by granting credit.

Borrowing money from the Banque de France was important to smooth the flow of tax payments, but in the overall picture of state finances it was a relatively small contribution to war financing. [...] While the emperor's borrowing from the Banque was generally limited, the government pressed the bank too far on one occasion, forcing a partial suspension in 1805.

Bordo & White: "British and French Finance During the Napoleonic Wars"

Napoleon presented himself to the public as an opponent of credit and even paid soldiers directly in coin. Given the monetary debacle during the French Revolution, this is hardly surprising.

Napoleon is traditionally regarded by historians as a simple, stubborn and ''hard-money'' man. In public, he spoke out vehemently against any new debt. [...] The result of his new policy was that the French were taxed much more heavily than before the Revolution.

Bordo & White: "British and French Finance During the Napoleonic Wars"

England

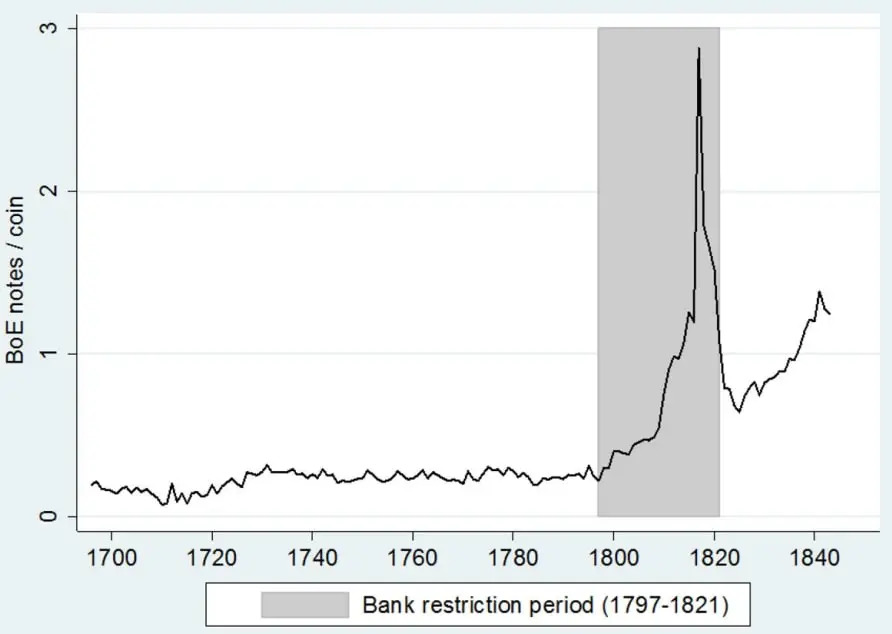

After France had already declared war in 1792, England rearmed. 90 percent of the expenditure before the start of the war was covered by loans - a doubling of the national debt within a few years was the consequence. The fear of an invasion by France finally triggered a bank run in 1797. The Bank of England then suspended the convertibility of banknotes into gold and banned coin payments - printing presses sprang up:

Prior to 1797, the Bank of England had operated five printing presses, but by March 16, 1797, it had 16 printing presses operating day and night, plus 14 more to come.

O'Brien & Palma: "The Bank of England and the British economy, 1694-1844"

Inflation ensued and the banknotes depreciated against other currencies. However, hyperinflation was averted and in 1821, after a successful victory, the banknotes were once again exchangeable for gold. This was possible because the bank continued to collect gold during the suspension period and people had not completely lost their trust in the bank. The government also took measures during the war to collect more taxes - for example, income tax was introduced in England in 1799.

Germany

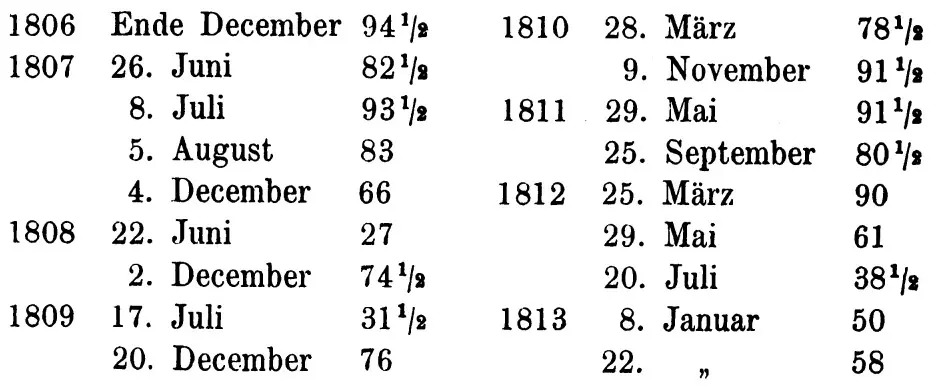

After the Germans had observed what had happened to the assignats during the French Revolution, they were all the more skeptical about paper money. In the face of the impending war, the government finally changed its mind. Paper money was issued for the first time in Prussia in 1806. The so-called Tresorscheine, which could initially still be exchanged for silver coins, were finally subject to compulsory acceptance.

The wars from the French Revolution to the fall of Napoleon resulted in various local issues of emergency money, such as the siege bills of Mainz, Kolberg and Erfurt and money-like vouchers from various military offices.

of various military offices. From 1806, the Prussian state issued paper money under the name "Tresorscheine", prompted by the war emergency.

Federal Bank

After several defeats in the war and the French occupation of Brandenburg and Silesia, redeemability was finally suspended. The value of paper money rose and fell in line with developments on the battlefield.

Although additional Thaler bills were issued in 1810, the money supply was not expanded unchecked. Redeemability was restored in 1813 and the paper money was destroyed over time.

Austria

At the end of the Seven Years' War (1756 - 1763 ), Austria introduces paper money called Bankozettel.

The main reason for issuing paper money was the enormous costs of the Seven Years' War with Prussia. The possibilities of raising new debts from domestic and foreign banks or the estates of the crown lands were coming to an end, most state revenues had already been pledged and, in addition, the interest burdened the budget enormously. Thus, increasing the circulation of money through paper money, the proverbial printing of money, was seen as a way of generating additional funds at almost no extra cost.

Austrian State Archives

Just a few years later, further bank notes were issued. As previously issued banknotes were destroyed again, the expansion of the money supply was initially limited. Due to an ever-increasing state deficit, banknotes were finally issued in secret during the Russo-Austrian Turkish War (1787 - 1792) and circulating silver coins were debased.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the issue of banknotes finally got completely out of control.

[...] Through further, uncontrolled issues in 1796, 1800 and above all from 1806, the total circulation of banknotes issued rose to over one billion guilders by 1810, and the path to national bankruptcy was mapped out. The exchange rate against the coinage fell rapidly, and the decline in value reached over 80 percent compared to the nominal value.

Austrian State Archives

During the period of severe currency devaluation, the prices of goods rose to immeasurable heights. Austrians speculated on real estate and those who bought jewelry also profited greatly. In 1811, Austria declared state bankruptcy and the bank notes could be exchanged at a ratio of 5:1 for the new paper money(redemption bills), which was also soon to be heavily exploited despite promises of scarcity. It was not until around 20 years later that it was again possible to exchange paper money for silver, as promised.

American Civil War (1861 - 1865)

In the period before the American Civil War, a system of private banks was established in the USA that issued paper money exchangeable for gold or silver. If a bank issued too much uncovered paper money, there was a high probability of bankruptcy if too many people wanted to exchange the money - there were no systemic bank bailouts. Privately issued paper money therefore became completely worthless if the issuing bank speculated. Paper money issued by the state was highly undesirable, at least since the dilemma with the Continentals of the War of Independence.

In 1860, the Republican Abraham Lincoln became President of the United States. As Lincoln spoke out against slavery, a conflict broke out between the northern and southern states of the USA. Some southern states, which still supported slavery, seceded from the USA and founded the Confederate States of America in 1861, with Jefferson Davis as president. Lincoln was against this secession and armed conflict was the consequence.

The northern states (Union) were in a much better financial position than the southern states (Confederacy). Nevertheless, the costs of war were hugely underestimated in the North. At first, the Union tried to finance the war through tax increases and loans - but by 1861, government spending was already more than ten times higher than before the war.

Union

In July 1861, the government finally issued the first paper money since the War of Independence. Initially so-called demand notes with a value of 50 million US dollars - these were to be exchangeable for coin dollars ''on demand''. In December of the same year, however, the exchangeability was already suspended and the demand notes lost value. The following year, they were made the official means of payment.

As the demand notes were not enough to cover the costs of the war, additional United States Notes were issued in 1862. These were ultimately completely uncovered paper money.

In a cabinet meeting, Lincoln jokingly suggested that the United States Notes should not be inscribed with ''In God We Trust'' like the dollar coins, but with the biblical quotation ''Silver and Gold I have none, but such as I have I give to thee'', which means ''Silver and gold I have none, but what I have I give to thee''.

Since both the demand and the United States notes, in contrast to the paper money of private banks, were also printed on the back - in green - they were called greenbacks.

[...] on February 25, 1862, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, which authorized the Treasury Department to issue $150 million worth of United States Notes. These were not backed by gold and were also "lawful money and a legal tender in payment of all public and private debts in the United States." [...] Because the greenbacks were not backed by gold, the Treasury Department could print them at almost zero cost and then use them to pay soldiers and buy goods without worrying that people might try to exchange the greenbacks for gold.

Wang: "Running the Machine: How Greenbacks Funded the Union and Nationalized Its Currency"

The greenbacks eventually became legal tender, which could not be accepted - and of course the money supply was further expanded to finance the war.

By 1864, $415 million worth of U.S. bills were circulating throughout the North, more than double the nation's bills at the start of the war.

Wang: "Running the Machine: How Greenbacks Funded the Union and Nationalized Its Currency"

The US Congress ultimately authorized the issuance of United States Notes up to a volume of 450 million US dollars.

Confederation

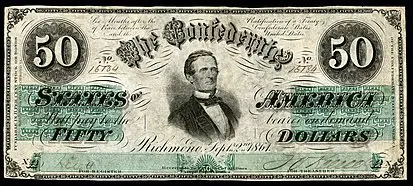

But the other party to the war, the Confederate States of America, also resorted to issuing uncovered paper money during the war. It issued the banknotes for the first time in 1861, immediately before the outbreak of the war. Colloquially, they were called greybacks to distinguish them from greenbacks. Some banknotes stated that they could be exchanged for coins after the war.

The decline in value of the Greybacks was enormous and comparable to that of the Continentals from the War of Independence. They lost significantly more value than the greenbacks. There were several reasons for this: First, because the war went in favor of the Union and because the Confederacy, unlike the Union, did not declare their bills as official currency. In addition, the Confederacy expanded the money supply far more than the Union did.

By printing more than twice as much paper money as the Union, the Confederacy experienced exponentially higher inflation. By the end of the war, inflation in the Union was only 80%, while in the Confederacy it was 9,000%.

Wang: "Running the Machine: How Greenbacks Funded the Union and Nationalized Its Currency"

Due to the strong devaluation of the Greybacks, some people in the southern states even preferred to use the enemy currency. Also, hardly anyone wanted to sell their gold for Greybacks. President Davis could think of nothing better than to ask his citizens to offer products at heavily discounted prices in order to counteract the fall in the price of Greybacks.

New currency system emerges

Even though the greybacks were a far greater disaster than the greenbacks, at the lowest point 258 units of the latter had to be put on the table for 100 gold dollars - a devaluation of over 60 percent. It took more than 20 years before the greenbacks could be exchanged for gold at an exchange rate of 1:1 - the greybacks, the currency of the war losers, became completely worthless.

The USA ultimately used the war and the government's issuance of fiat money as an opportunity to centralize the monetary system. Although the US central bank had not yet been established, the USA created the National Bank Act during the war - a decisive step away from free banking towards a state banking system.

On February 25, 1863, President Lincoln signed the National Currency Act. This act established the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), which was responsible for organizing and administering a system of state-chartered banks and a uniform national currency. In June 1864, the Act was substantially amended and became the National Bank Act. The National Bank Act has been amended and supplemented over the years and remains the basic framework for the national banking system today.

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

Interim conclusion

The issue of paper money by the state is closely linked to the financing of war - even civil wars. The examples in the second part of the article series should have shown this. Whether the fiat money became completely worthless after the war or could be exchanged again for the equivalent value in gold or silver depended not only on the extent of the expansion of the money supply but also on the outcome of the war.

With all the examples, we are still at the underpinning of the first argument that hard money, or even the unpreventable competition from it, could make government fundraising for warfare on both sides immensely more difficult. Bitcoin differs fundamentally from gold in this respect: Bitcoin is far more difficult to ban and, in its basic form, more suitable for transactions. This is also demonstrated by the failure of gold as money in the 20th century.

To complete this argument, we will also take a closer look at the First and Second World Wars in the next article. However, we can already tell you that this argument will not stop there.