In the first and second parts of this series of articles, we saw that states debased coins and, in the recent past, increasingly introduced unbacked paper money to cover the costs of war.

The expansion of the money supply also played a decisive role in the major wars of the last century. However, most observers of these wars focus primarily on the war bonds issued, which the warring states used to borrow from the population. This type of financing, together with tax increases, was nowhere near enough to pay for the most expensive and destructive wars in human history, each of which caused tens of millions of deaths.

This part of the article series is intended to show that it is a mistake to claim that the world wars would have been possible in this form under hard and free money. For the First World War, after a long period of relative peace and prosperity, the gold standard was abolished in most industrialized nations. Even during the Second World War, none of the belligerent nations had a currency that was exchangeable for gold. The central banks concentrated primarily on providing financial support for the respective war - independence was effectively abolished.

Pax Britannica (1815 - 1914)

After the Napoleonic Wars (1799 - 1815), the then world power Great Britain returned to the gold standard. To be more precise, it was only at this time that a real gold standard began on the island, as silver had always been used as a means of payment before the wars. Over time, a number of countries followed suit. A period of stability and relative peace began - at least in the western world - which is commonly referred to as Pax Britannica (in German: British Peace). There were still wars in Europe, but they were relatively short.

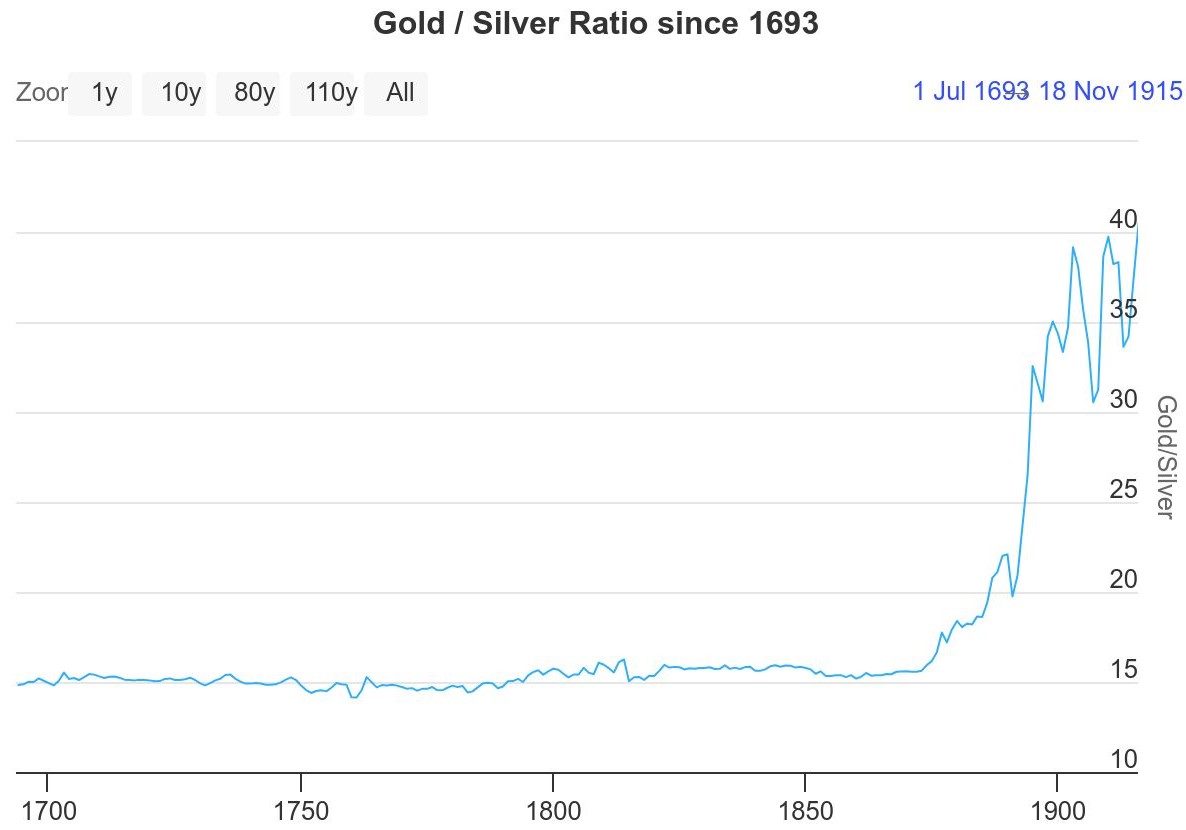

For the short Franco-Prussian War (1870 - 1871), the issue of uncovered paper money was not used. Germany won the war and had France pay the reparations in gold. The gold received in this way became the basis for the gold-backed German mark. With Germany on a gold standard, the monetary system became established throughout the western world. The USA also turned its back on silver and when, 24 years after the American Civil War, greenbacks could once again be exchanged for gold, the United States was also effectively on a gold standard. The price of gold, measured in silver, doubled within three decades.

The period of the classical gold standard (1871 - 1914) was ultimately the time of high industrialization. The automobile, the light bulb, the airplane and the telephone were invented. It was a period of decent economic growth, rising wages and a stock market with an above-average inflation-adjusted return. All this "even though" goods prices fell most of the time.

World War I (1914 - 1918) and the abandonment of the gold standard

This period came to an end with the First World War. Most belligerent nations abolished the exchangeability of currency for gold. But even countries that were not directly involved in the war, such as Denmark, used it as an opportunity to stop exchanging banknotes for the precious metal themselves.

Great Britain

Before the First World War, the British superpower was in a very strong financial position: The national debt was relatively low at around 30 percent of annual economic output and the tax burden for the British was low. For the First World War, however, Great Britain had to run up huge debts. The convertibility of banknotes into gold was abolished and between 1914 and 1919 the national debt increased more than tenfold, resulting in a national debt of over 150 percent.

The USA and Canada granted the British large loans, some of which were never paid. However, it was also important to borrow from the British population by means of war bonds. The bonds were heavily advertised: People were to benefit financially from them in the long term as well as, of course, helping the fatherland.

Sir Gordon Narin, the then Chief Cashier of the Bank of England, swore on oath that the public had bought all the war bonds. However, as it turned out around 100 years later, despite the propaganda, the public only bought far less than a third of the first war bonds.

On November 23, 1914, an article appeared in the Financial Times claiming that the British government's war bonds were "oversubscribed" and that applications were "pouring in". The article described this as an "astonishing result" which "proves how strong is the financial position of the British nation". We are now pleased to clarify that none of this is true.

Financial Times (2017)

In reality, the British central bank bought up the remaining bonds and skillfully hid this on its balance sheet. The war bonds were listed by the Bank of England under the heading "other securities" and not "government securities".

Incidentally, John Maynard Keynes was working at the British Treasury at this time. Keynes is the founder of Keynesianism, a school of economic thought that argues that governments should play an active role in economic policy. Keynesianism continues to shape the economy and the role of the state in it to this day. In a secret memo to the British Treasury in 1915, Keynes described the trick as a "masterly manipulation". This was decisive in enabling the UK to find investors for further war bonds in 1917.

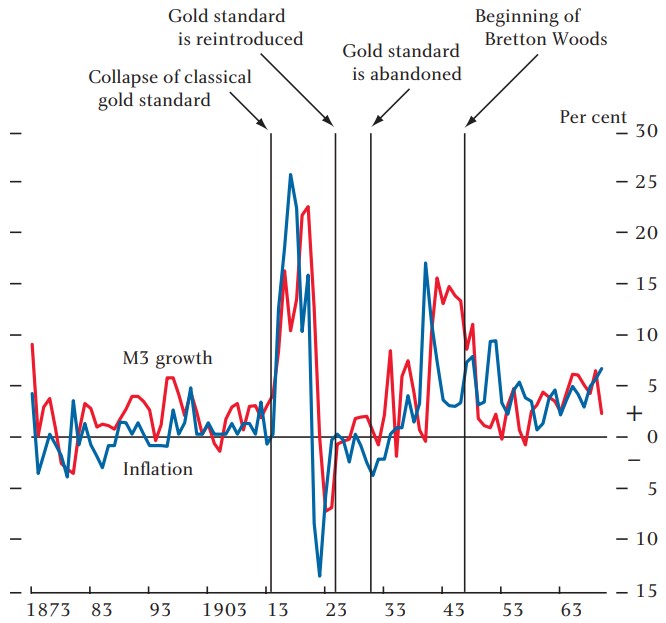

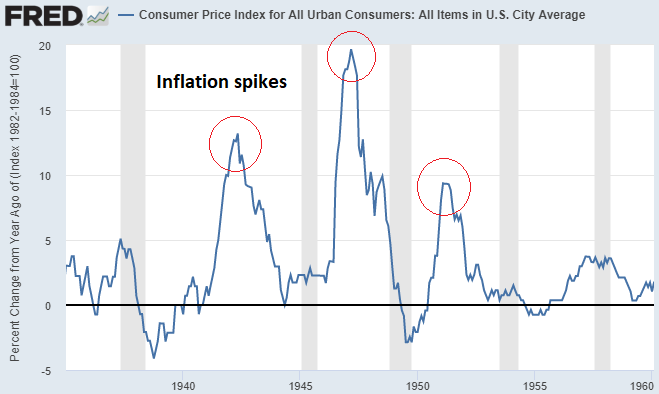

As the central bank was buying up the bonds and the gold standard had been abolished, it is hardly surprising that the money supply in Britain exploded hand in hand with the price of goods. Before the war, there was still slight deflation - inflation rates of well over 20 percent at the end of the war.

In 1925, Great Britain returned to the gold standard. The British pound was pegged to the US dollar at the same pre-war exchange rate, which was still exchangeable for gold. However, as the official exchange rate was set too high due to the previous expansion of the money supply, i.e. the British pound was overvalued, the return to the gold standard led to a deflationary economic crisis.

France

France, which was fighting on the side of Great Britain, left the gold standard at the beginning of the war. There are some parallels to Great Britain in terms of war financing, with the only difference being that France was more heavily in debt and less able to cover war expenditure with tax revenues. Accordingly, France had to print more money, which led to higher inflation - even after the war. France did not return to the gold standard until ten years after the war. In contrast to Great Britain, the franc was pegged to gold at a lower rate than before the war - France admitted to the loss in value.

[...] long-term debt and fiscal resources could not cover the level of expenditure required by an all-out war lasting more than four years. The difference was made up by printing money and short-term debt - i.e. monetary resources - which led to inflation. [...] Thus the money supply and prices rose fourfold during the war and by a further 25 percent in the post-war period, leading [President] Poincaré to stabilize the franc at 20 percent of its pre-war value in gold in 1928.

Baubeau: "War Finance (France)"

USA

Reaction to the banking crisis in 1907, in which the convertibility of the US dollar into gold had already been suspended by the government. While officially remaining neutral, the US supported the Allies, particularly France and Great Britain, in the early years of the war by granting them large loans. The US economy benefited from the war, as a lot of gold flowed from Europe to the States, which was sometimes used to buy weapons and munitions.

In 1917, the Allies were in a difficult position and the USA decided to become an active party to the war itself. Not least out of concern that the loans previously granted would not be repaid if the Allies were defeated. After entering the war, US monthly government spending increased well over twenty-fold and the newly established Federal Reserve was on hand:

And as the nation entered the war, the Fed devoted itself primarily to supporting the war effort.

Federal Reserve History

War bonds(Liberty bonds & Victory bonds) were also to play a major role in the USA. The Federal Reserve favored banks that bought war bonds by granting them loans at better conditions. There was also immense social pressure to buy the bonds. After the first issue, war bonds immediately lost value - presumably because many bought them simply to express their patriotism, but not out of conviction.

The bonds enabled the USA to cover a considerable part of the war costs. Further funds were raised through taxes, but also by expanding the money supply.

The majority of the war effort (58 percent) was therefore financed by borrowing from the public. The remainder was divided roughly equally between taxes (22 percent) and money creation (20 percent).

Rockoff: "The U.S. Economy in World War 1"

Even though the US dollar was exchangeable for gold throughout the war, unbacked paper money, i.e. fiat money, was used to finance the war - with the support of the Federal Reserve.

When the United States entered World War I, the basis of monetary expansion shifted from gold to fiat money, as the newly created Federal Reserve monetized a significant portion of the debt issued. In this respect, the inflationary pressures were similar to those generated by the issuance of greenbacks during the Civil War. Thus, the World War I expansion is best viewed as a combination of the two preceding long expansions: a gold-backed peacetime expansion from 1914 to 1917, similar to the gold-backed peacetime expansion of the early 1850s, and a "paper-backed" wartime expansion from 1917 to 1918, similar to the paper-backed expansion of the Civil War.

Rockoff: "The U.S. Economy in World War 1"

In the period from 1915 to 1920, the money supply in the US doubled, resulting in a loss of purchasing power of the US dollar of almost 50 percent.

The result of all these machinations was significant inflation, which fluctuated between 13% and 20% for most of the war, higher than the 1% inflation rate recorded in the Fed's first year. In 1920, a dollar could buy about half the goods it could buy in 1914.

Koning: "How the Fed Helped Pay for World War I"

Germany

In Germany, the situation around the First World War was precarious. Germany's savings would only have been enough for two days of war and tax revenues could only cover an even smaller proportion of war expenditure than in Great Britain. Accordingly, Germany had to take on massive amounts of debt. However, as Germany had less developed capital markets than Great Britain and was unable to find foreign lenders, its options were limited.

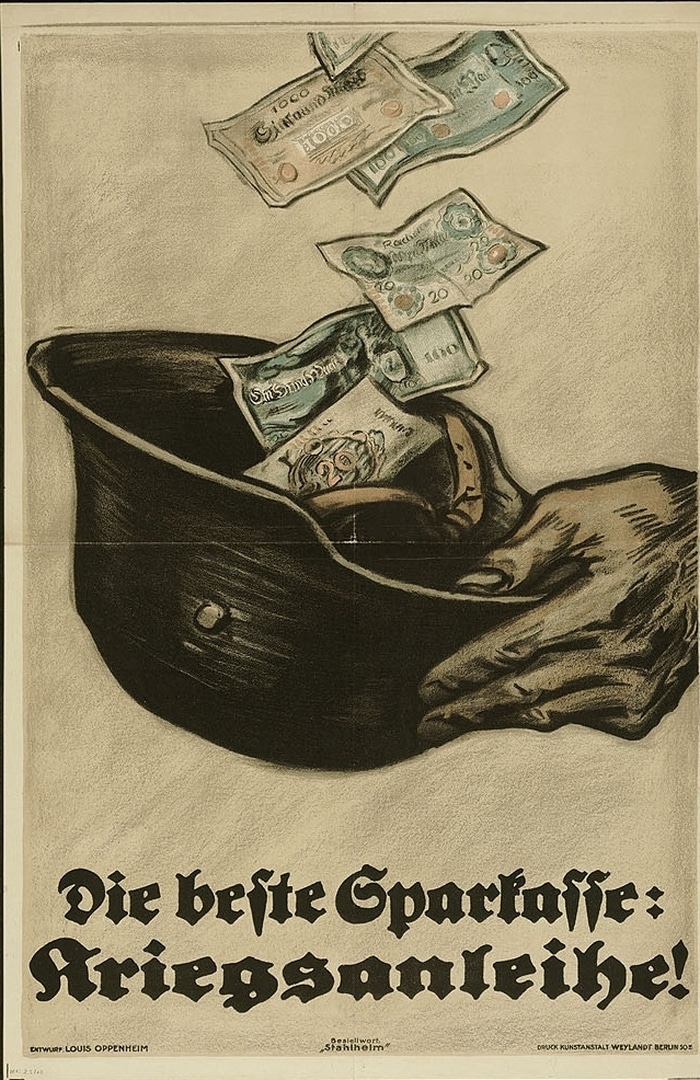

The efforts to raise loans from their own population were great - the propaganda was running at full speed:

And when a big Zeppelin flies over London and drops a heavy fat bomb on the London bank [...] or when a submarine lobs a shell into the black belly of an enemy ammunition steamer, [...] then you bang your fist on the table and say: 'I helped pay for that, bombs and shells I helped pay for.

Leaflet from 1916

In addition to the moral aspect, the propaganda was also aimed at the financial aspect. The bonds were described as the "best savings bank" and with the lavish reparation payments from the Franco-Prussian War in mind, some citizens were won over to this investment.

Although the propaganda in Germany bore fruit, the population's money was nowhere near enough to cover the high costs of the war. Accordingly, Germany's own central bank had to act as a lender - with newly created money. The Reichsbank's obligation to exchange paper marks for gold marks at any time was already suspended at the beginning of the war.

By 1917, only a quarter of the bonds were held by the market; three quarters were held by the Reichsbank [...]. The explanation for the rapid expansion of the monetary base must therefore be sought in the lack of market demand for the bonds, which led to the majority of them being monetized directly at the Reichsbank.

Balderston: "War Finance and Inflation in Britain and Germany, 1914-1918"

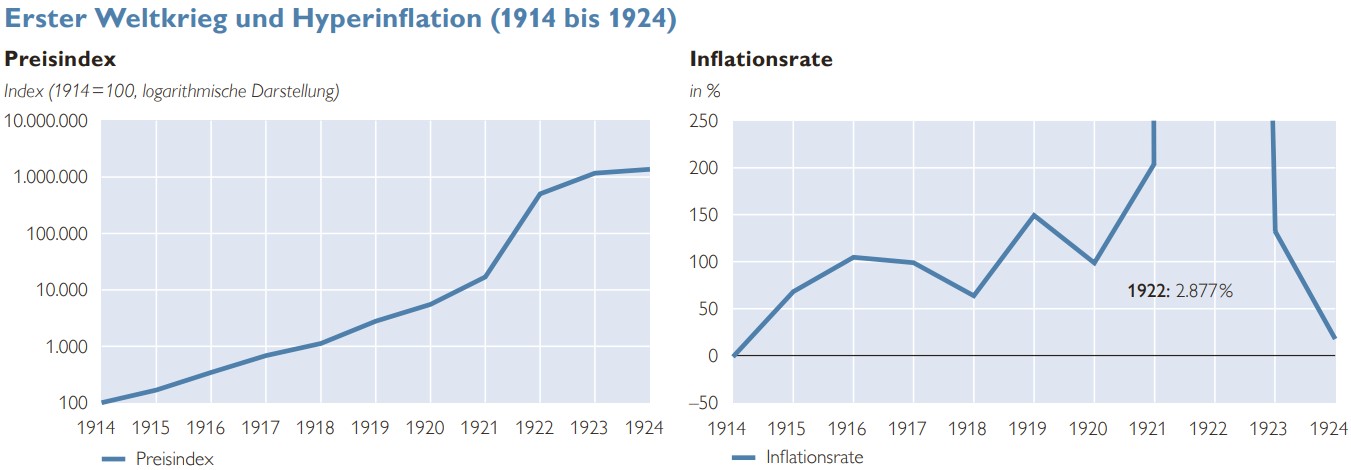

Hyperinflation 1923

Germany's war financing was inferior to that of Great Britain: greater recourse had to be made to printed money, as the costs of the war could be borne by a significantly lower proportion of taxes and loans. Germany's money supply increased accordingly.

At the end of 1917, the German monetary base was already almost 3.5 times as high as at the end of 1913; in Great Britain it was less than twice as high. The money supply in Germany at the end of 1917 was 2.54 times what it had been at the end of 1913; in Britain it was 1.68 times.

Balderston: "War Finance and Inflation in Britain and Germany, 1914-1918"

The reason why inflation accelerated sharply in Germany after the war, while it fell again on the island, is that there was no end to the expansion of the money supply in Germany. Germany had to find a lot of money after the war. On the one hand, to pay reparations, which the defeated Germany was obliged to pay under the Treaty of Versailles, in gold and foreign currencies. Secondly, to settle the loans and to meet payment obligations to its own population, such as pensions for soldiers.

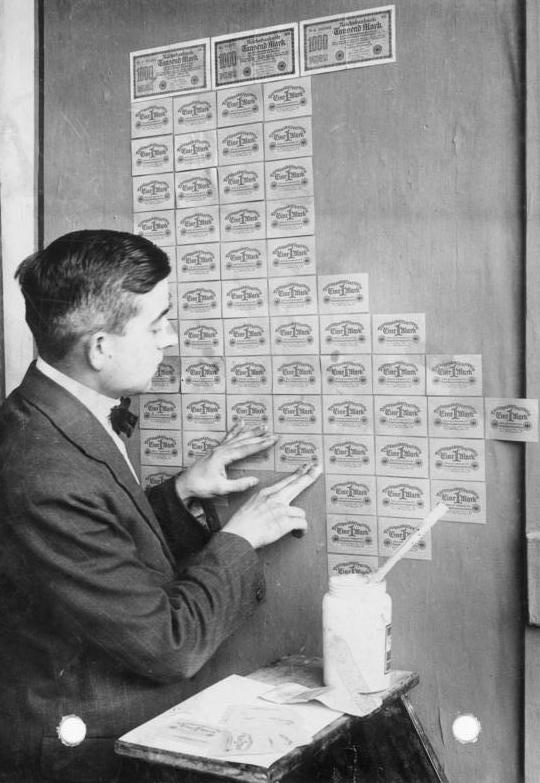

Over 1,800 printing presses run around the clock to constantly push new banknotes onto the market; almost 30,000 people are employed in the production of new banknotes.

Losse: "Billions for bread"

In 1921, the depreciation of the paper mark accelerated further when Germany began printing money to buy foreign currency to pay reparations. A few months later, the paper mark was virtually worthless and as no one wanted to exchange currencies for it, Germany had to continue paying off its debts to foreign countries with raw materials such as coal.

At the beginning of 1923, the Ruhr area was occupied by France and Belgium due to the lack of reparations payments. The government urged the workers to go on strike and promised to continue paying them anyway - with newly printed money.

The paper mark was ultimately worth so little that people reckoned in bundles, transported money in wheelbarrows for payment and papered the walls with it.

At the height of hyperinflation, Germany banned the possession of gold, silver and foreign currency. There were even raids on stores to confiscate the forbidden means of payment.

Germany was impoverished and the people were starving. The way out was a currency reform: Germany introduced the Rentenmark at an exchange rate of one trillion paper marks to one Rentenmark. In addition, the printing presses were shut down and the granting of credit by the central bank to the state was stopped.

The ban on foreign exchange trading was lifted in 1926 and the ban on gold and silver was not lifted until 1931.

So it was the German population that ultimately paid for the burdens and debts of the First World War. [...] The biggest profiteer was the state. Its total war debt of 154 billion marks amounted to just 15.4 pfennigs when the new currency, the Rentenmark, was introduced on November 15, 1923.

Delveaux de Fenfee: "The hyperinflation of 1923"

Austria

In Austria, war financing and its consequences were similar to those in allied Germany.

In August 1914, key parts of the National Bank's statutes were repealed, including the statutory minimum cover of banknotes in circulation by gold and the clause prohibiting the National Bank from granting loans to the state. Banknotes in circulation increased 12-fold between mid-1914 and the end of the First World War.

Austrian National Bank

As in Germany, Austria experienced hyperinflation in the post-war years, which was ended by a currency reform. The prices of goods rose more than ten thousand-fold compared to pre-war levels.

While hyperinflation reduced the state's debt burden, it also impoverished the holders of war bonds and thus the middle class.

Austrian National Bank

Second World War (1939 - 1945)

After the sometimes quite severe inflation of the First World War, the belligerent states had to become a little more imaginative in order to finance the Second World War. Ultimately, however, there was again no way around a strong expansion of the money supply. It was therefore convenient that the USA, Germany, Austria, Great Britain, France, etc., withdrew from gold at the beginning of the 1930s. In the early 1930s, the USA, Germany, Austria, Great Britain, France etc. had already abandoned the gold standard - officially as a reaction to the Great Depression. In the USA, private ownership of gold worth more than 100 US dollars was therefore banned as early as 1933. Citizens had to hand in their gold at a rate of 20.67 US dollars per troy ounce at state collection points.

Germany

After the monetary debacle surrounding the First World War, the German state had to dig particularly deep into its bag of tricks to finance the Second World War. War bonds would probably hardly have been subscribed to by the population. It was also not possible to simply print the necessary money straight away, because the hyperinflation of the 1920s was still fresh in the minds of the Germans - a looming high inflation rate would probably have been quickly exacerbated by panic among the population itself.

With the beginning of the Nazi era in 1933, Germany began to arm itself. The state procured the funds for this through a sophisticated concept:

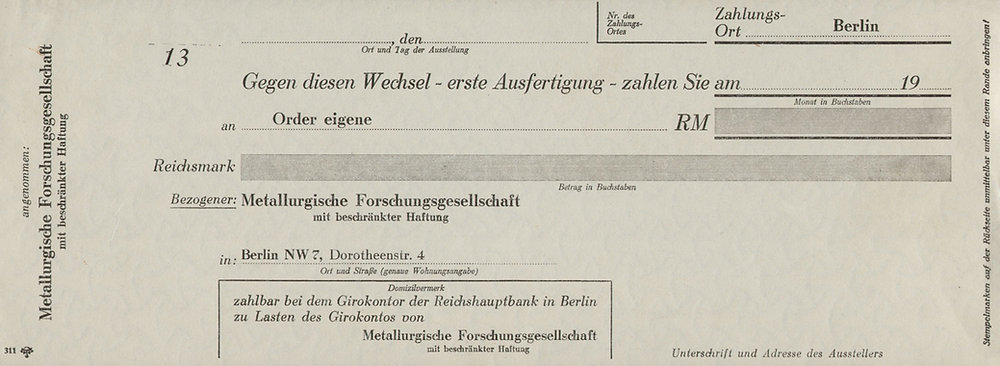

The president of the Reichsbank introduced the so-called Mefo bills. These were effectively government cheques that could be exchanged for Reichsmarks within five years. Industry accepted these bills and used them itself for payments. They thus developed into a means of payment.

At the time of the wedding, 12 billion Reichsmark Mefo bills were in circulation. In addition, there were also Öffa bills, which the Nazi regime used for state building projects and job creation measures. More than one billion Reichsmarks of the Öffa bills were in circulation.

Ultimately, the introduction of the bills of exchange was a hidden national debt, as they did not appear in the budget. With the Metallurgische Forschungsgesellschaft m. b. H. (Mefo) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für öffentliche Arbeiten AG (Öffa), Germany founded dummy companies for this purpose.

The bills in circulation inflated the money supply to finance the war, whereas the official money supply had been kept fairly stable before the outbreak of war. In a letter to Adolf Hitler, the Reich Finance Minister also described the bills of exchange as money creation.

Since the assumption of power, a conscious decision was made to finance the large one-off expenses of the initial job creation and rearmament by taking out loans. Insofar as this could not be achieved through the normal use of the money and capital markets, i.e. the annual increase in savings in Germany, the financing was carried out by means of bills of exchange (labor and moneys bills), which were discounted at the Reichsbank, i.e. through money creation.

Count Schwerin von Krosigk

In 1936, Germans had to exchange their gold for Reichsmarks at the Reichsbank - violations were punishable by death. In 1939, when war broke out, Germany also confiscated the precious metals of commercial companies. Furthermore, the Reichsbank was then placed directly under the control of Adolf Hitler and he obliged it to grant him any credit. This meant that bills of exchange could be exchanged for which there would otherwise have been no money. Nonetheless, one priority was to ensure that the Reichsmark did not lose too much confidence and that inflation did not degenerate. To this end, Hitler also forced the banks to grant loans to the state. At the beginning of the war, tax vouchers(N.F. tax vouchers) and short-term government bonds were also used to pay the government.

In 1941, the Nazi regime then launched another savings program, the Iron Savings Program. This created incentives for citizens to transfer part of their income directly to a savings account, which they were supposed to be able to access again no later than one year after the war. The state directly withdrew around 1.3 billion Reichsmarks from the money raised by this program.

In retrospect, all these measures are described as silent war financing. The Nazi regime was able to suppress inflation to some extent by forcing people to lend money to the state and providing incentives to save money, i.e. to consume less. Germany also used price controls to conceal inflation. To this end, there was a Reich Commissioner for Pricing who could close stores or put people in prison if, in his opinion, they raised prices too high. In the context of the Second World War, this is also referred to as disguised inflation.

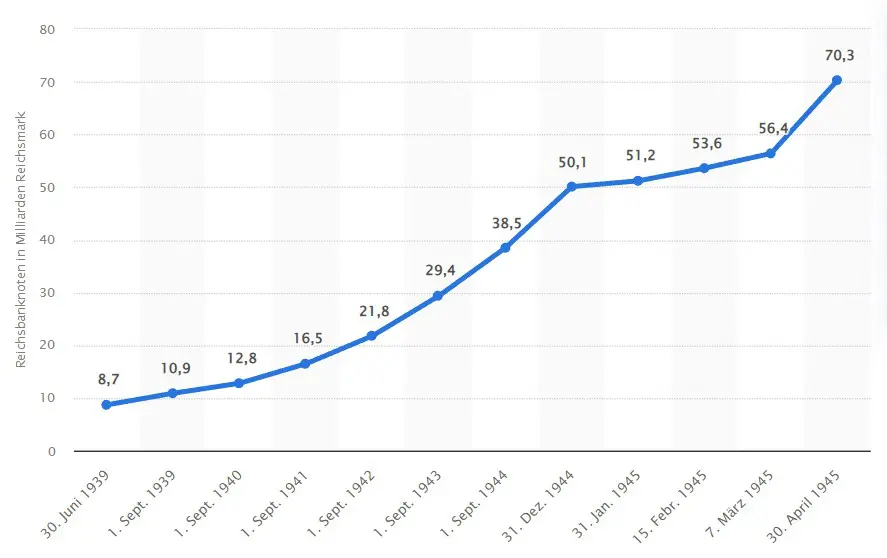

Despite all the macabre tricks, the official money supply multiplied during the war and inflation increased. The way out was ultimately a currency reform - Germany introduced the Deutschmark.

By 1945, the amount of central bank money (currency in circulation plus deposits at the Reichsbank) had risen to more than seven times its 1938 value.

Jürgen Stark (ECB)

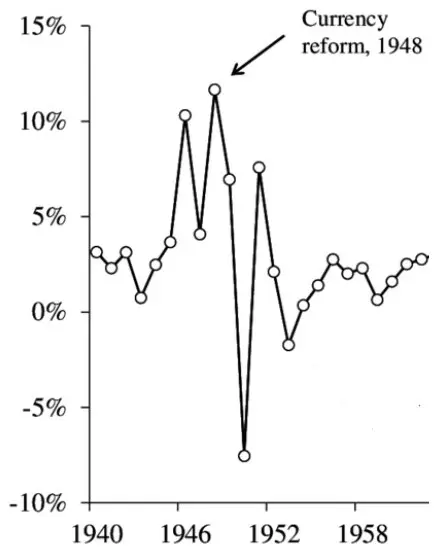

During the Second World War, the war effort was financed by government debt to the central bank and the resulting sharp increase in the money supply. Price freezes, wage fixing, rationing and ration coupons prevented inflation from becoming visible. Nevertheless, the massive devaluation of money led to a currency reform in 1948, in which the D-Mark was introduced and exchanged for Reichsmarks at a ratio of 1 to 10. Savers and owners of financial assets found themselves expropriated to a large extent.

Federal Bank

USA

In the USA, the Federal Reserve again played an extremely important role in financing the war. Tax revenues were of course not enough, although income tax for those earning over 200,000 US dollars was at times as high as 94 percent. The USA had to go into debt. Firstly, through war bonds, for which, of course, there was a lot of advertising. There were incentives for buyers of war bonds, such as free days at the movies. A special feature was that war bonds(stamps) could be bought for as little as 10 dollar cents. Well-known personalities and even Bugs Bunny publicly called for the purchase of war bonds:

Despite the success of the war bonds and the large tax increases, the US had to borrow largely from its own central bank.

As a result of the war effort, the US debt to GDP ratio rose from 40% to 110%, most of which was financed by the Fed's purchase of government bonds.

Atlanta Fed

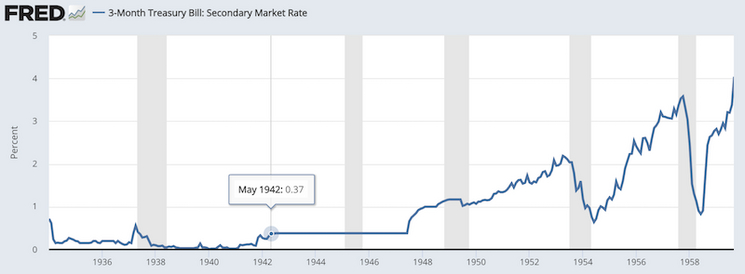

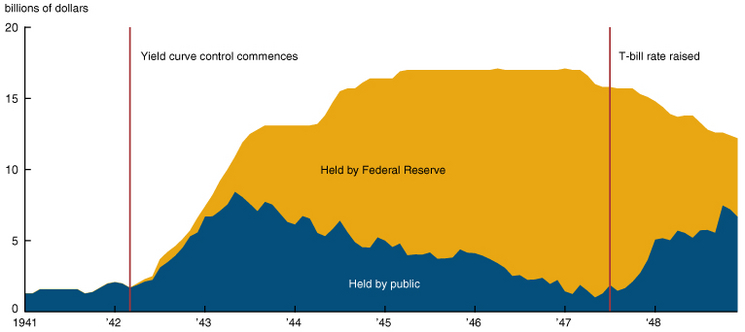

To prevent the USA from having to pay huge amounts of interest on the mountain of debt, the Federal Reserve used the monetary policy instrument of yield curve control for the first time. This means that the Fed bought as many government bonds as necessary to keep interest rates at the desired low level. As a result, the proportion of government bonds held by citizens fell dramatically. The Fed began this monetary policy measure around six months after the USA entered the war in December 1941.

In order to keep the costs of the war within reasonable limits, the Treasury Department asked the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates low. The central banks agreed to buy government bonds at an interest rate of 0.375%, which was well below the usual peacetime interest rate of 2 to 4 percent. The interest rate peg came into force in July 1942 and lasted until June 1947.

Federal Reserve History

The Federal Reserve was so preoccupied with war financing that more and more employees had to be hired to perform monetary acrobatics.

The twelve Federal Reserve Banks and their 24 branches played a significant role in this effort, and their work on behalf of the government expanded throughout the war. In 1939, the Reserve Banks employed about 11,000 people. In 1943 and 1944, the number of Reserve Bank employees reached a wartime high of more than 24,000.

Federal Reserve History

A doubling of the money supply and strong waves of inflation were ultimately the consequence.

Other countries

As war financing was ultimately always very similar, it should suffice at this point to take a brief look at a few of the other participants in the war.

In Great Britain, inflation rates of over 10 percent were observed during the war. In France, the situation was even worse: during and immediately after the war, inflation was sometimes around 50 percent.

Germany's allies had to deal with even higher inflation rates. In Japan, inflation was around 40 to 80 percent from quarter to quarter towards the end of the war. Austria and Hungary, on the other hand, both drifted into hyperinflation, with Hungary's being even more severe.

Pax Americana (1945 - ?)

After the Second World War, a kind of gold standard was reintroduced with the Bretton Woods system. The US dollar was exchangeable for gold at a fixed exchange rate (for foreign central banks) and the other countries in turn pegged their currencies to the US dollar at fixed exchange rates. At the same time, a period of relative peace began again - at least in the West - which is referred to as Pax Americana (American Peace).

Summary

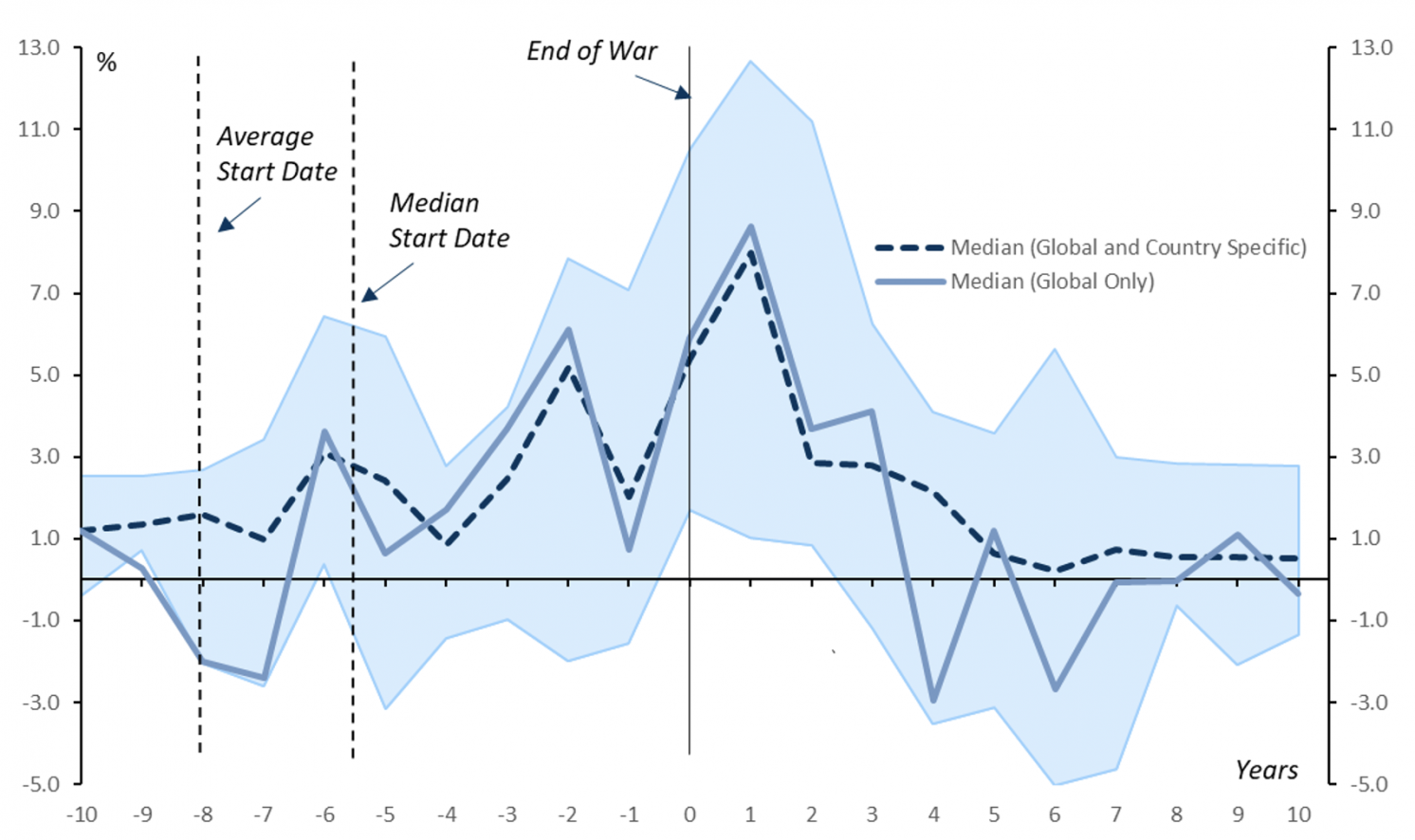

The world wars make it clear that although war financing became ever more inventive, there was no way around expanding the money supply in order to finance the most expensive wars in human history. Rather, the numerous tricks were aimed at obtaining funds without completely losing confidence in the most important weapon - one's own currency.

Increasing taxes immeasurably, forcing banks to give money to the state, expropriating citizens directly and forcing people to fight in wars would almost certainly not have been enough to make such deadly wars possible.

The world wars also make it clear that central banks are only ever "independent" until the population also has to be expropriated through the back door by expanding the money supply in order to wage war.

The fact that wars are generally accompanied by the devaluation of money or inflation and that this also applies to the two world wars should have been demonstrated by the series of articles up to this point.

However, this does not mean that wars are impossible with Bitcoin. Even if the amount of Bitcoin cannot be inflated centrally, a state could theoretically continue to collect taxes and convince citizens to lend it their Satoshis to wage war.

It is virtually impossible to predict what a world with Bitcoin as money might actually look like in the end, but it stands to reason that wars would at least be a lot "softer" - more on this in the next part of the article series.

Preview

Bitcoin is far more than just a money that cannot be centrally expanded to finance wars. Bitcoin could also revolutionize the way war is waged.

What makes Bitcoin so remarkable is that it appears to have created a non-lethal equivalent to warfare that achieves the same complex, evolving benefits of traditional warfare by utilizing the exact same social protocol of physical power competition [...] but it removes the mass in those power competitions and exchanges it with energy, eliminating the ability for human injury and intraspecies fratricide.

Lowery: "Softwar"